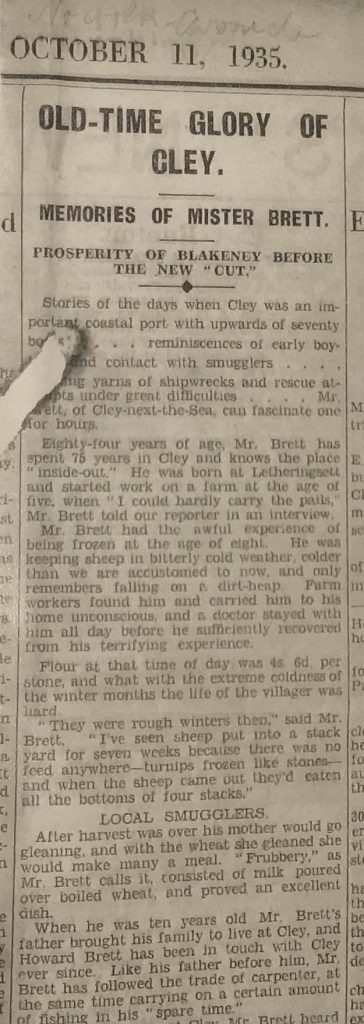

OLD-TIME GLORY OF CLEY.

Memories of Mister Brett

Prosperity of Blakeney before the New ‘Cut’

The following is a transcript of an interview published on 11 October 1935 with Howard Brett from the Norfolk Chronicle.

Stories of the days when Cley was an important coastal port with upwards of seventy boats … Reminiscences of early boyhood and contact with smugglers … thrilling yarns of shipwrecks and rescue attempts under great difficulties … Mr Brett of Cley-next-the-Sea, can fascinate one for hours.

Eighty-four years of age, Mr Brett has spent 75 years in Cley and knows the place ‘inside out. He was born at Letheringsett and started work on a farm at the age of five, when ‘I could hardly carry the pails‘ Mr Brett told our reporter in an interview.

Mr Brett had the awful experience of being frozen at the age of eight He was keeping sheep in bitterly cold weather, colder than we are accustomed to now, and only remembers falling on a dirt-heap. Farm workers found him and carried him to his home unconscious, and a doctor stayed with him all day before he sufficiently recovered from his terrifying experience.

Flour at that time was 4s 6d per stone, and what with the extreme coldness of the winter months the life of the villager was hard.

‘They were rough winters then,’ said Mr Brett. ‘I’ve seen sheep put into a stack yard for seven weeks because there was no feed anywhere – turnips frozen like stones – and when the sheep came out they’d eaten all the bottoms of four stacks.’

Local Smugglers

After harvest was over his mother would go gleaning, and with the wheat she gleaned she would make many a meal. ‘Frubbery,’ as Mr Brett calls it, consisted of milk poured over boiled wheat, and proved an excellent dish.

When he was ten years old Mr Brett’s father brought his family to live at Cley, and Howard Brett has been in touch with Cley ever since. Like his father before him, Mr Brett has followed the trade of carpenter, at the same time carrying on a certain amount of fishing in ‘his spare time.’

In his early years at Cley, Mr Brett heard a lot about the smuggling that was carried on, but he came in contact with the smugglers very little. ‘There was always someone to guard the place where they stored their stuff’ he said, and ‘they looked out that you didn’t see too much.’

He remembers seeing a quantity of cases in a pit hole on Cley allotments once, and when next morning he and some other boys went to pry into the matter they found the cases gone and strange marks through the snow. The horses’ hooves had been bound with sacks by the cautious smugglers!

Shipwreck of 1880

Mr Brett belonged to the Cley Rocket Company for over 30 years and has a medal for 25 years’ service.

But more than that, he treasures the bronze medal given him by the French Government for rescuing a lad of 19 from the St. Joseph Dunkerque which was wrecked off Cley in the morning of November 19th, 1880.

Mr Brett remembers the circumstances vividly. It was a bitterly cold morning when the two-masted schooner came ashore, and the marshes were frozen and covered with snow. The ship was laden with gasometers and lamp-posts and had a crew of five. The men of the Cley Rocket Company set to work, but the crew of the French vessel did not understand the working of the breeches buoy. Three were drowned and two taken off, but one alone survived. Brett’s brave rescue work is best described in his own words:-

“There was a French boy on the deck and I could hear him crying for help. I couldn’t stand it I went out to him, and the water froze like a knife and poured over me. I got on to the ship by climbing up a rope, and put the boy in the breeches buoy and they pulled him ashore.” It appears that the lad was taken to the King’s Head in a frozen condition and died. The four Frenchmen lie in Cley churchyard.

Mr Brett has taken part in many rescues off Cley.

Sailed into the King’s Head Yard

He remembers ten Germans being taken off a wreck and put in a crab-boat which sailed right into the King’s Head yard! This was when the whole marshes and village were flooded. The worst night he remembers was during the War when, as a man of about 65, he went with the Rocket Company to Blakeney Point to a wreck which had been cleared of its crew unbeknown to the Cley Brigade.

One ship which went ashore at Cley was saved from total wreckage by the wits of a shipbroker who hired men to dig the stones and sand away from the vessel, and then constructed a dock with the aid of guano bags filled with stones. When the tide came in the vessel floated out to sea.

Often employed at Blakeney as a ship’s carpenter, and also making coffins when the occasion arose, Mr Brett became an expert at his trade. While working on the ships at Blakeney as a lad he acquired the knack of shinning up a rope ‘hand over fist’, and this stood him in good stead in latter days as a life-saver.

Twelve children Mr Brett had to bring up, and this necessitated his ‘drawing the shore’ at night to earn a few extra shillings. His boat ‘Chance’ has been his sole companion for many a long-drawn night Often Mr Brett would snatch about two hours’ sleep and then hurry off to his carpenter’s shop for his day’s work. Those hard days gave Mr Brett no chance of luxuries, and that is why he is a non-smoker and practically a non‑drinker today.

70 Ships in Cley Channel

“Big ships used to come up to Blakeney and Cley then,” Mr Brett told our reporter, “and I can remember when there were over 70 boats at Cley alone.” That was in the days of the old Cley channel (now silted up near the beach), but since the new ‘cut’ was constructed no ships have been up to the Quay. Generally, however, the big vessels would be in Blakeney Pit and lighters would ply between Cley Quay and the Pit, a distance of three miles. Mr Brett has helped to push lighters to the Pit laden with 45 tons of corn which had to be substituted for 45 tons of coal and brought back to Cley. Four men manned these lighters which were pushed along with the aid of long poles. It took about fourteen hours to get to Blakeney and back again to Cley and shift 90 tons of corn and coal. Mr Brett is rather proud of this feat. “Where would the chaps be now,” he asked, his bearded face alight with superiority, “if they had to do it? I often tell them they don’t know what work is.”

Cley did a fair trade in oil cake in Mr Brett’s young days, and the Quay was a busy place. In the High Street there was formerly a bone-manure factory, and huge quantities of bones used to come up to the Quay.

In his time Mr Brett has built many small boats, and he still has his carpenter’s shop, although he does not work in it now.

Longshore Salmon

The best stroke of fishing business Mr Brett ever did took place at Cromer. He and a mate caught some salmon, which they took to Cromer in their boat. A gentleman hailed them and offered 1s 6d a pound for their catch. Mr Brett and his mate, who had almost given up hope of selling the fish, gladly accepted and left Cromer with the sum of £10 6s!

Mr Brett remembers almost all the old craft of Cley and their owners, but as he says, “there is nothing done now.” Mr Brett has six children alive but his wife has been dead some years.